Marino di Teana was a man of many angles. Born in 1920 in the medieval village of Teana, Italy, he lived and worked as a shepherd when he was very young and was raised mostly by his grandparents after his father ran off to Argentina. He led an isolated childhood, amusing himself by drawing on the walls of the barn where he played alone by day.

When his grandparents couldn’t afford to send him to school, they arranged for him to apprentice with a decorator from Naples and then with a master mason. He worked hard and became adept at making his own tools, forging them himself.

When he was 16, di Teana went to live and work in Argentina, reuniting with the father he barely knew and who wanted him to be an architect rather than a starving artist. But following years with a brutal work schedule—he even recalled helping build coaches for Peron's labor festival—during which time he also took night classes, he escaped to Europe, spending time in Spain, Italy, and France, chasing art, architecture, and art history.

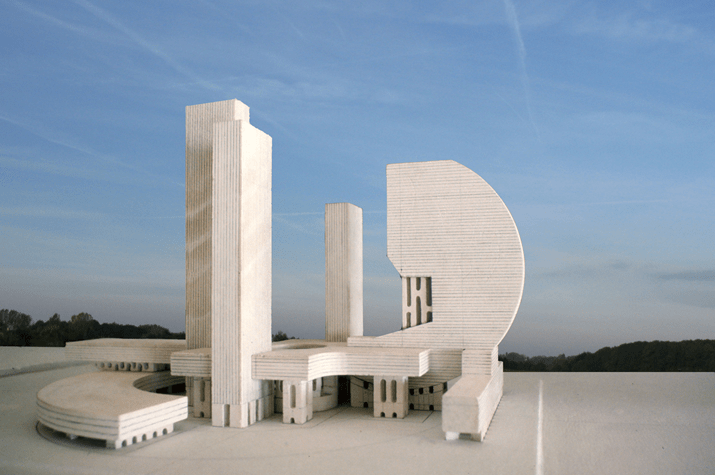

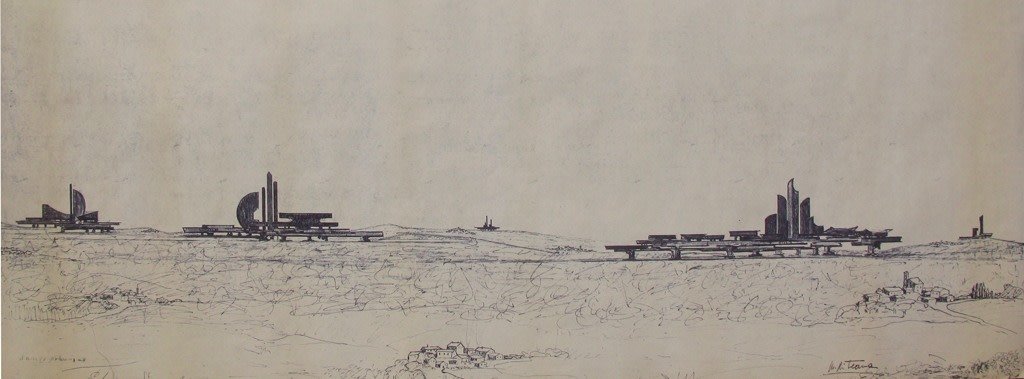

He wrote that Europe would give him the opportunity to see the arts in their own setting. “A piece of carved stone,” he wrote, “is really beautiful only in its relation to the church, to the village, to the country.” This seems like a maxim governing all of his work—its physical and cultural context.

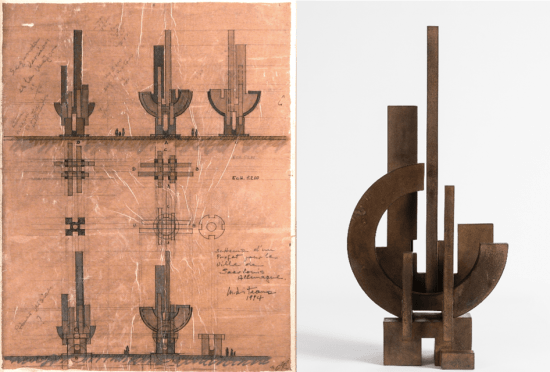

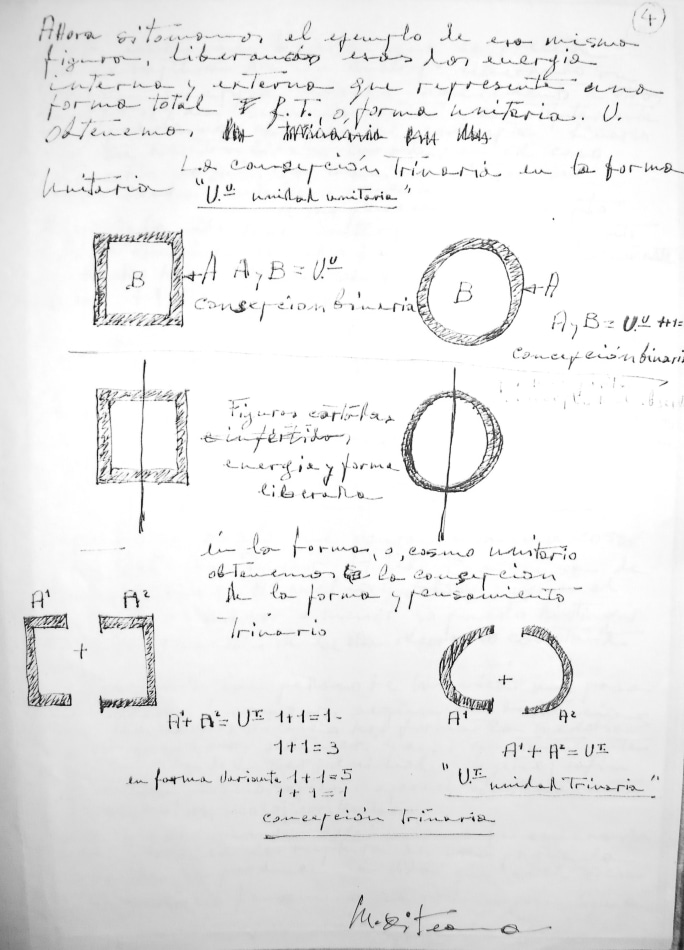

What is fascinating about di Teana is how familiar his work seems at first look and yet how difficult it can be to place, attributable perhaps to the fact that he fits comfortably in several genres and time periods.

All sorts of odds and ends made their way into his art, from the drawings he made as a child, including obsessive sketches of Mussolini, to his compulsively executed sculptures. “I was constantly messing in clay,” he recalled. He would also pick up and store rocks and build with them.